Perishable News

Media Society Council member Ivor Gaber on how news has changed. Issue #3

Welcome to the Media Society’s latest Substack newsletter. This edition’s article was written by Ivor Gaber - a British academic and journalist, and former professor of political journalism at University of Sussex.

It was while leafing through a recent edition of the British Journalism Review, reading about the history of The Media Society, that I noticed that my entry into the world of journalism coincided with the launch of the Society. It made me reflect on the nature of ‘news’.

It was 1972 and I was in my first job since leaving university as Deputy Editor (and teaboy) on Drugs and Society, a quarterly magazine about what, appeared to be, the growing problem of drug abuse – although compared to the situation today, there was hardly a problem at all.

And although I enjoyed my stint in the world of magazines, I really wanted to be a TV journalist. At the time, there were just three TV channels in the UK – BBC1, BBC2 and ITV. Based on my ‘vast experience’ at producing a student TV programme at university, I had assumed that I would be seen as gold dust by the TV newsroom bosses.

I was wrong. I was turned down by the BBC and ITN – not to mention every single radio station I could locate.

But I did eventually manage to break into TV news, courtesy of a company then known as Visnews (now Reuters TV), which distributed TV news clips around the world. Visnews was a joint venture of Reuters, the BBC, and the public service broadcasters of Canada, Australia and New Zealand - a rather ‘olde worlde’ set-up.

Then, as now, TV stations in Europe and the US received the majority of their foreign news clips through three daily Eurovision news exchanges, with the material being transmitted via the Eurovision network. But the majority of the company’s clients received their clips in a box that was flown out to them on a daily basis from London.

If this might seem a rather clunky method of distributing ‘up-to-the-minute’ news, it was positively jet-aged compared to what, following a posting to Sydney, I was to learn about how the news reached our clients in Australia.

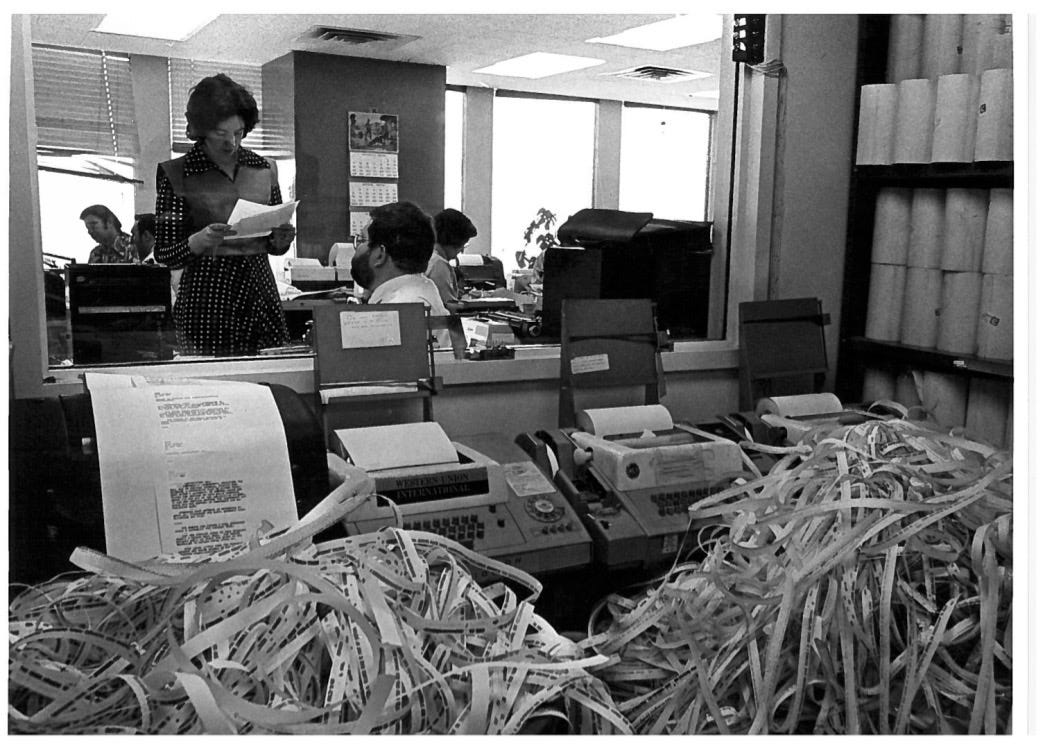

My morning would begin by working on a list sent by telex (remember them – machines that transmitted type strokes inputted by someone in one part of the world which could be received by someone, perhaps thousands of miles away).

My morning telex would contain a list of news stories – all on film - that a few hours before had been shipped from London to Australia, which, after expanding and updating the story list, I would then send on to our clients in Australia’s main cities, asking which were of interest to them.

Later that morning, the clips would arrive – bearing in mind that because of the time difference and the length of the flight - they were already at least two days old. They would be brought by taxi from the airport to the laboratories.

The clips were in the form of ‘dupe negs’ – duplicates of the original negatives - that would be used to print as many copies as were required. These would then be shipped back to the airport for distribution. Stations in Sydney obviously had no problems airing these clips on the same day – stations in Melbourne and Brisbane had a good chance, stations in Adelaide, a reasonable chance and those in Perth in Western Australia (a five-hour flight from Sydney) only a fighting chance.

So, the nightly news in much of Australia involved coverage that could be days out of date (bearing in mind that the original film would have taken at least a day to reach London). For very big stories, the Australian stations could club together, and I could arrange a satellite transmission of a clip or clips, but that cost a lot of money - $3,000, which was then a considerable sum, so it was a rarity.

Today, of course, news is instantaneous. Coverage doesn’t have to go through news wholesalers, i.e. the broadcasters, but can be consumed directly - the live streaming of the massacre of 51 people in a mosque in New Zealand back in 2019 was perhaps the first major story that was distributed this way.

So, are we any better off by seeing ‘news’ now, as it happens, rather than by waiting a few hours, or even a few days?

I’m reminded of a conversation I had some years ago with a woman who was head of news at a local radio station in a small town in Uganda. I was, as part of a consultancy, quizzing her about how her stations gathered news; she told me that most news stories arrived in the form of hand-written notes.

Noticing there was a computer in the newsroom, I asked why her correspondents didn’t file by email – “Oh, they never have” was her reply, as if it was obvious.

“But surely” I replied, “if they filed by email your listeners would hear today’s news today?”

She looked at me quizzically: “But it doesn’t matter when they hear the news, nor when it happened – if they hear it today then, for them, that’s the latest news.”

It was then my turn to look quizzical – she had a point. Was it important that, for instance, viewers in Perth, back then, saw news that was then three or more days old?

Probably not, after all, just as with the horrific shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand, there was nothing that anyone watching the stream could do about it - so it was with the viewers in Perth. If this was the first time they were viewing an event, then for them it was ‘news’ – it was probably only the broadcasters who cared.

The Media Society is a British charity that organises events that discuss and debate important and topical media issues.

Join the Media Society - and help us with our work, and, at the same time, receive valuable benefits. Find out more about joining here.

In 1865, after Abraham Lincoln was shot, Reuters got the scoop, but it still took twelve days for the news to reach Europe. First the news flash was transmitted by telegraph from Washington

to New York. But the next mail steamer heading for Europe was not due to leave until the following afternoon, so the Reuters man in New York chartered a fast tug boat to chase after a steamer that had left a few hours earlier. It caught up, and a canister containing the Lincoln

dispatch was thrown on board. Once the steamer had crossed the Atlantic, the canister was transferred onto a smaller vessel off the west coast of Ireland, so that the news could then be transmitted onwards via telegraph. And because Julius Reuter had laid his own private telegraph line that reached further west – to Crookhaven – than the commercial line that stopped at Cork, he could get the news onto the telegraph several hours before anyone else.

Interesting reflections, Professor Gaber.